Navegation

Primitive Christianity home pageBohemian Revival

IntroductionPart 1 Birth Pangs

Part 2 Birth

Part 3 Maturity

Part 4 Sick unto Death

Part 5 Burial

Part 6 The Hidden Seed

Part 7 Lessons from the Bohemians

Download the PDF-3mb

John Augusta: Joining Hands with Protestantism

As Bishop Luke lay dying at Mlada Boleslav, there was rising to fame among the Big Group the most brilliant and powerful leader they had ever known. Again we turn to the old Teyn Church; again the preacher is denouncing the priests; and again in the pew is an eager listener with soul aflame with zeal. The listeners name was John Augusta. He was born, in 1500, at Prague. His father was a hatter, and in all probability he learned the trade himself. He was brought up in the Utraquist faith; he took the sacrament every Sunday in the famous old Teyn Church; and there he heard the preacher declare that the priests in Prague cared for nothing but comfort, and that the average Christians of the day were no better than crack-brained heathen sprinkled with holy water. The young man was staggered; he consulted other priests, and the others told him the same dismal tale. One loaned him a pamphlet, entitled “The Antichrist”;106 another lent him a treatise by Huss; and a third said solemnly: “My son, I see that God has more in store for you than I can understand.”

However, the strangest event of all was still to come. As he rode one day in a covered wagon with two Ultraquist priests of high rank, it so happened that one of them turned to Augusta and urged him to leave the Utraquist Church and join the ranks of the Big Group at Mlada Boleslav. Augusta was horrified!

Again he consulted the learned priest; again he received the same strange counsel; and one day the priest ran after him, called him back, and said: “Listen, dear brother! I beseech you, leave us. You will get no good among us. Go to the Brethren at Mlada Boleslav, and there your soul will find rest.”

Augusta was shocked beyond measure. He hated the Brethren, regarded them as beasts, and had often warned others against them. But now he went to see them himself, and found to his joy that they followed the Scriptures, obeyed the Gospel107 and enforced their rules without respect of persons. For a while he was in a quandary. His conscience drew him to the Big Group, his honor held him to the Utraquists, and finally his own father-confessor settled the question for him.

“Dear friend,” said the man, “entrust your soul to the Brethren. Never mind if some of them are hypocrites, who do not obey their own rules. It is your business to obey the rules yourself. What more do you want? If you return to us in Prague, you will meet with none but sinners and sodomites.”

And so, by the advice of Utraquist priests, this ardent young man joined the ranks of the Brethren, was probably trained in the Brethren’s house at Mlada Boleslav, and was soon ordained as a minister. Forthwith he rose to fame and power in the pulpit. His manner was dignified and noble. His brow was lofty, his eye flashing, his bearing the bearing of a commanding king. He was a splendid speaker, a ready debater, a ruler of men, an inspirer of action; he was known ere long as the Bohemian Luther; and he spread the fame of the Brethren’s Church throughout the Protestant world.

Full soon, in truth, he began his great campaign. As he entered on his work as a preacher of the Gospel, he found that among the younger Brethren there were quite a number who did not feel at all disposed to be bound by the warning words of Luke of Prague. They had been to the great Wittenberg University; they had mingled with Luther’s students; they had listened to the talk of Michael Weiss, who had been a monk at Breslau, and had brought Lutheran opinions with him; they admired both Luther and Melancthon; and they now resolved, with one consent, that if the candlestick of the Brethren’s Church was not to be moved from out its place, they must step shoulder to shoulder with Luther, become a regiment in the conquering Protestant army, and march with him to the goodly land where the flower of the ‘glad free Gospel bloomed in purity and sweet perfume.’

At the first opportunity Augusta, their leader, brought forward their views. At a Synod held at Brandys nad Orlici—summoned by John Augusta’s friend, John Horn, the senior Bishop of the Big Group, for the purpose of electing some new Bishops—Augusta rose to address the assembly. He spoke in the name of the younger clergy, and immediately commenced an attack upon the old Executive Council. He accused them of listlessness and sloth; he said that they could not understand the spirit of the age, and he ended his speech by proposing himself and four other broad-minded men as members of the Council. The old men were shocked; the young were entranced; and Augusta was elected and consecrated a Bishop, and thus, at the age of thirty-two, became the leader of the Big Group. He had three great schemes in view:

Friendly relations with Protestants in other countries.

Legal recognition of the Brethren in Bohemia.

The union of all Bohemian Protestants.

First, then, with Augusta to lead them on, the Big Group brethren enlisted in the Protestant army. As the Protestants in Germany had issued the Confession of Augsburg, and had it read in solemn style before the face of the Emperor, Charles V, so now the Big Group issued a new and full “Confession of Faith,” to be sent first to George, Margrave of Brandenburg, and then laid in due time before Ferdinand, King of Bohemia.

Peter Chelcicky and Gregory would have “turned over in their grave!” Joining in the military and mixing Church and State!

Even now the Big Group did not, like Luther, lay stress on the doctrine of 'justification by faith alone'. And yet Luther had no fault to find with this Confession. It was addressed to him, was printed at Wittenberg, was issued with his consent and approval, and was praised by him in a preface. It was read and approved by John Calvin, by Martin Bucer, by Philip Melancthon, by pious old George, Margrave of Brandenburg, and by John Frederick, Elector of Saxony. Again and again the Big Group sent deputies to see the great Protestant leaders. At Wittenberg, Augusta discussed good morals with Luther and Melancthon; and at Strasburg, Cerwenka, the Big Group’s historian, held friendly counsel with Martin Bucer and Calvin. Never had the Bohemian Brethren been so widely known, and never had they received so many compliments. Formerly Luther, who liked straight talk, had called the Brethren “sour-looking hypocrites and self-grown saints, who believe in nothing but what they themselves teach.”

But now he was all good humor. “There never have been any Christians,” he said, in a lecture to his students, “so like the apostles in doctrine and constitution as these Bohemian Brethren.”

“Tell your Brethren,” he said to their deputies, “to hold fast what God has given them, and never give up their constitution and discipline. Let them take no heed of revilements. The world will behave foolishly. If you in Bohemia were to live as we do, what is said of us would be said of you, and if we were to live as you do, what is said of you would be said of us.” “We have never,” he added, in a letter to the Brethren, “attained to such a discipline and holy life as is found among you, but in the future we shall make it our aim to attain it.”108

The other “great Reformers” were just as enthusiastic. “How shall I,” said Bucer, “instruct those whom God Himself has instructed! You alone, in all the world, combine a wholesome discipline with a pure faith.”

“We,” said Calvin, “have long since recognized the value of such a system, but cannot, in any way, attain to it.”

“I am pleased,” said Melancthon, “with the strict discipline enforced in your congregations. I wish we could have a stricter discipline in ours.”

Meanwhile Augusta pushed his second plan; Legal recognition of the Big Group. The task before him was gigantic. A great event had taken place in Bohemia. At the battle of Mohacz, in a war with the Turks, Louis, King of Bohemia, fell from his horse when crossing a stream, and was drowned.109 The old line of Bohemian Kings had come to an end. The crown fell into the hands of the Hapsburgs—the fervent supporters of the Church of Rome. The King of Bohemia, Ferdinand I, was likewise King of Hungary, Archduke of Austria, King of the Romans, and brother of the Emperor Charles V, the head of the Holy Roman Empire.

For the Big Group the situation was momentous. As Augusta scanned the widening view, he saw that the time was coming fast when “the brethren”, whether they wanted to or not, would be called to “play their part like men” in a vast European conflict. Already the Emperor Charles V had threatened to crush the Reformation by force; already the Protestant princes in Germany had formed the Smalkald League; and Augusta, scenting the battle from afar, resolved to build a 'fortress' for the Brethren.

His policy was clear and simple. If the King of Bohemia joined forces with the Emperor, the days of the Big Group would soon be over. So he, John Augusta, would make the King of Bohemia their friend, and thus save them from destruction.

For this purpose, Augusta now instructed the powerful Baron, Conrad Krajek, the richest member of the Big Group, to present their Confession of Faith to King Ferdinand. The Baron undertook the task. He was the leader of a group of Barons who had recently joined the Church; he had built the great Zbor of the Brethren in Mlada Boleslav, known as “Mount Carmel”; he had been the first to suggest a Confession of Faith, and now, having signed the Confession himself, he sought out the King at Vienna, and was admitted to a private interview.110

The scene was stormy. “We would like to know,” said the King, “how you Brethren came to adopt this faith. The devil has persuaded you.”

“Not the devil, gracious liege,” replied the Baron, “but Christ the Lord through the Holy Scriptures. If Christ was a Picard, then I am one too.”

The King was beside himself with rage.

“What business,” he shouted, “have you to meddle with such things? You are neither Pope, nor Emperor, nor King. Believe what you will! We shall not prevent you! If you really want to go to hell, go by all means!”

The Baron was silent. The King paused.

“Yes, yes,” he continued, “You may believe what you like and we shall not prevent you; but all the same, I give you warning that we shall put a stop to your meetings, where you carry on your hocus-pocus.”

The Baron was almost weeping.

“Your Majesty,” he protested, “should not be so hard on me and my noble friends. We are the most loyal subjects in your kingdom.”

The King softened, spoke more gently, but still held to his point.

“I swore,” he said, “at my coronation to give justice to the Utraquists and Catholics, and I know what the statute says.”

As the King spoke those ominous words, he was referring, as the Baron knew full well, to the terrible Edict of St. James. The interview ended; the Baron withdrew; the issue still hung doubtful.

And yet the Baron had not spoken in vain. For three days the King was left undisturbed; and then two other Barons appeared and presented the Confession, signed by twelve nobles and thirty-three knights, in due form.

“Do you really think,” they humbly said, “that it helps the unity of the kingdom when priests are allowed to say in the pulpit that it is less sinful to kill a Picard than it is to kill a dog.”

The King was touched; his anger was gone, and a week later he promised the Barons that as long as they, the Big Group, were loyal subjects, he would allow them to worship as they pleased.

For some years the new policy worked very well, and the King kept his promise. The Big Group’s numbers were extending on every hand. They had now at least four hundred churches and 200,000 members. They printed and published translations of Luther’s works. They had a church in the city of Prague itself. They enjoyed the favor of the leading nobles in the land; and Augusta, in a famous sermon, expressed the hope that before very long the Brethren and Utraquists would be united and form one National Protestant Church...111

Unexpected Reverse

At this point something did take a turn for the better. As the Big Group was now so friendly with Luther, there was a danger that they would abandon their discipline—what was left of it— and become ashamed of their own little Church, and try to totally imitate the teaching and practice of their powerful Protestant friends. For some years after Bishop Luke’s death, they actually gave way to this temptation, and Luke’s last treatise, “Regulations for Priests,” was scornfully cast aside.

However, the The Big Group soon returned to their senses—at least a little. As John Augusta and John Horn traveled in Germany, they made the strange and startling discovery that, after all, the Brethren’s Church was better off than their Protestant friend’s churches. For a while they were dazzled by the brilliance of the Lutheran preachers; but in the end they came to the conclusion that although these preachers were clever men, they had not so firm a grip on Divine truth as the their own preachers. At last, in 1546, the Big Group met in a Synod at Mlada Boleslav to discuss the whole situation. With tears in his eyes, John Horn addressed the assembly. “I have never understood until now,” he said, “what a costly treasure our Church is. I have been blinded by the reading of German books! I have never found any thing so good in those books as we have in the books of the Brethren. You have no need, beloved Brethren, to seek for instruction from others. You have enough at home. I exhort you to study what you have already; you will find there all you need.”

Again the church discipline was revived in vigor112; again, by Augusta’s advice, the Catechism of Luke was put into common use, and the Brethren began to open schools and teach their principles to others.

But now their fondest hopes were doomed to be blasted. For the last time Augusta went to Wittenberg to discuss the value of discipline with Luther, and as his stay drew to a close he warned the man that if the German theologians spent so much time in spinning doctrines and so little time in teaching morals, there was danger brewing ahead.

The warning soon came true. The Reformer died. The gathering clouds in Germany burst, and the Smalkald War broke out. The storm swept on to Bohemia. As the Emperor gathered his forces in Germany to crush the Protestant Princes to powder, so Ferdinand in Bohemia summoned his subjects to rally round his standard at Litomerice and defend the kingdom and the throne against the Protestant rebels. For the first time in their history, the Bohemian Brethren were ordered to take sides in a civil war.

The situation was delicate. If they fought for the Catholic King Ferdinand, they would be untrue to their faith; if they fought against him, they would be disloyal to their country.

As soon as they could possibly do so, the Big Group elders issued a form of prayer to be used in all their churches. It was a prayer for the kingdom and the throne. But meanwhile, others were taking definite sides. At Litomerice, the Catholics and old-fashioned Utraquists mustered to fight for the King; and at Prague the Protestant nobles met to defend the cause of religious liberty. They met in secret at a Big Group member’s house; they formed a Committee of Safety of eight, and of those eight, four were Big Group members. They passed a resolution to defy the King, and send help to the German Protestant leader, John Frederick, Elector of Saxony.

And then the retribution fell like a bolt from the blue. The great battle of Muhlberg was fought;113 the Protestant troops were routed; the Elector of Saxony was captured; the Emperor was master of Germany, and Ferdinand returned to Prague with vengeance written on his brow. He called a council at Prague Castle, summoned the nobles and knights before him, ordered them to deliver up their treasonable papers, came down on many with heavy fines, and condemned the ringleaders to death.

The Wages of Rebellion

At eight in the morning, August 22nd, four Barons were led out to execution in Prague. The scaffold was erected in a public place that all the people might see and learn a lesson. Among the Barons was Wenzel Petipesky, a member of the Big Group’s Church. He was to be the first to die. As he was led from his cell by the executioner, he called out in a loud voice, which could be heard far and wide: “My dear Brethren, we go happy in the name of the Lord, for we go in the narrow way.”

Narrow way? Since when did armed rebellion become the narrow way?

He walked to the scaffold with his hands bound before him while two boys played his dead march on drums. As he reached the scaffold the drums ceased, and the executioner announced that the prisoner was dying because he had tried to dethrone King Ferdinand and put another King in his place.

“That,” said Petipesky, “was never the case.”

“Never mind, my Lord,” roared the executioner, “it will not help you now.”

“My God,” said Petipesky, “I leave all to You.” And his head rolled on the ground.114

The worst was still to come. As Ferdinand came out of the castle church on Sunday morning, September 18th, he was met by a deputation of Utraquists and Catholics, who besought him to protect them against the cruelties inflicted on them by the ‘Picards’. The King soon eased their minds. He had heard a rumor that John Augusta was the real leader of the revolt; he regarded the Brethren as traitors; he no longer felt bound by his promise to spare them; and, therefore, reviving the Edict of St. James, he issued an order that all their meetings should be suppressed, all their property be confiscated, all their churches be purified and transformed into Romanist Chapels, and all their priests be captured and brought to the castle in Prague.

The Big Group brethren pleaded not guilty. They had not, as a whole body, taken any part in the conspiracy against the King. Instead of plotting against him, in fact, they had prayed and fasted in every parish for the kingdom and the throne. If the King, they protested, desired to punish the few guilty Brethren, by all means let him do so; but let him not crush the innocent many for the sake of a guilty few.

“My word,” replied the King, “is final.” The Brethren continued to protest. And the King retorted by issuing an order that all Brethren who lived on Royal estates must either accept the Catholic faith or leave the country before six weeks were over.115

Exodus

Ferdinand was astounded at the result of this decree. Unwilling to face persecution as an “illegal church”, thousands from the Big Group went over en masse to the Utraquists. A minority that refused, about 1500 people, fled on foot and in refugee wagon trains through Silesia to Poland. The Anabaptists fled east, to Hungary, and the Little Group, with the brothers at Habrovany116 simply disappeared.

The End of John Augusta

Meanwhile, John Augusta, the leader of the Big Group still in Bohemia, was passing through the furnace of affliction.

Of all the tools employed by Ferdinand, the most crafty, active and ambitious was a certain officer named Sebastian Schoneich, who, in the words of the great historian, Gindely, was one of those men fitted by nature for the post of hangman.

For some months this man had distinguished himself by his zeal in the cause of the King. He had seized sixteen heads of families for singing hymns at a baker’s funeral, had thrown them into the sewer drains of the White Tower at Prague, and had left them there to mend their ways in the midst of filth and horrible stenches. And now he occupied the position of town-captain of Litosmyl. For some time Augusta had been hiding in the neighboring woods, and only two or three Brethren knew his exact abode. Persecution had done her work, and treachery now did hers.

Among the inhabitants of Litosmyl were certain renegade Brethren, and these now said to the Royal Commissioners: “If the King could only capture and torture Augusta, he could unearth the whole conspiracy.”

“Where is Augusta?” asked the Commissioners.

“He is not at home,” replied the traitors, “But if you will ask his friend, Jacob Bilek, he will tell you all you want to know.”

The wily Schoneich laid his plot. If only he could capture Augusta, he would win the favor of the King and fill his own pockets with money. As he strolled one day through the streets of Litosmyl he met a certain innocent Brother Henry, and there and then began his deadly work.

“If you know,” he said, “where Augusta is, tell him I desire an interview with him. I will meet him wherever he likes. I have something special to say to him, something good, not only for him, but for the whole Unity. But breathe not a word of this to anyone else. Not a soul—not even yourself—must know about the matter.”

The message to Augusta was sent. He replied that he would grant the interview on condition that Schoneich would guarantee his personal safety.

“That,” replied Schoneich, “is quite impossible. I cannot give any security whatever. The whole business must be perfectly secret. Not a soul must be present but Augusta and myself. I wouldn’t have the King know about this for a thousand groschen. Tell Augusta not to be afraid of me. I have no instructions concerning him. He can come with an easy mind to Litosmyl. If he will not trust me as far as that, let him name the place himself, and I will go though it be a dozen miles away.”

But Augusta still returned the same answer, and Schoneich had to strengthen his plea. Again he met the guileless Brother Henry, and again he stormed him with his eloquent tongue.

“Have you no better answer from Augusta?” he asked.

“No,” replied Brother Henry.

“My dear, my only Henry,” pleaded Schoneich, “I do so long for a little chat with Augusta. My heart bleeds with sympathy for you. I am expecting the King’s Commissioners. They may be here any moment. It will go hard with you poor folk when they come. If only I could have a talk with Augusta, it would be so much better for you all. But do tell him not to be afraid of me. I have no instructions concerning him. I will wager my neck for that,” he said, putting his finger to his throat. “I am willing to give my life for you poor Brethren.”

The shot went home. As Augusta lay in his safe retreat he had written stirring letters to the Brethren urging them to be true to their colors; and now, he heard from his friends in Litosmyl that Schoneich was an evangelical saint, and that if he would only confer with the saint he might render his Brethren signal service, and deliver them from their distresses. He responded nobly to the appeal. For the sake of the Church he had led so long, he would risk his liberty and his life. In vain the voice of prudence said “Stay!”; the voice of love said “Go!”; and Augusta agreed to meet the Captain in a wood three miles from the town.

The Captain chuckled.

The time was fixed, and, the night before, the artful plotter sent three of his trusty friends to lie in wait. As the morning broke of the fateful day,117 Augusta, still suspecting a trap, sent his secretary, Jacob Bilek, in advance to spy the land; and the three brave men sprang out upon him and carried him off to Schoneich. And then, at the appointed hour, came John Augusta himself. He had dressed himself as a country peasant, carried a hoe in is hand, and strolled in the woodland whistling a merry tune. For the moment the hirelings were baffled. They seized him and let him go; they seized him again and let him go again; they seized him, for the third time, searched him, and found a fine handkerchief in his bosom.

“Ah,” said one of them, “a country peasant does not use a handkerchief like this.”

The game was up. Augusta stood revealed, and Schoneich, hearing the glorious news, came prancing up on his horse.

“My lord,” said Augusta, “is this what you call faith?”

“Did you never hear,” said Schoneich, “that promises made in the night are never binding? Did you never hear of a certain Jew with his red beard and yellow bag? Did you never hear of the mighty power of money? And where have you come from this morning? I hear you have plenty of money in your possession. Where is that money now?”

As they rode next day in a covered wagon on their way to the city of Prague, the Captain pestered Augusta with many questions.

“My dear Johannes,” said the jovial wag, “where have you been? With whom? Where are your letters and your clothes? Whose is this cap? Where did you get it? Who lent it to you? What do they call him? Where does he live? Where is your horse? Where is your money? Where are your companions?”

“Why do you ask so many questions?” asked Augusta.

“Because,” replied Schoneich, letting out the murder, “I want to be able to give information about you. I don’t want to be called a donkey or a calf.”

Augusta was now imprisoned in the White Tower at Prague. He was placed in the wine vaults below the castle, had heavy fetters on his hands and feet, and sat for days in a crunched position. The historic contest began. For two hours at a stretch the King’s examiners riddled Augusta with questions. “Who sent the letter to the King?” they asked. “Where do the Brethren keep their papers and money? To whom did the Brethren turn for help when the King called on his subjects to support him? Who went with you to Wittenberg? For what and for whom did the Brethren pray.”

“They prayed,” said Augusta, “that God would incline the heart of the King to be gracious to us.”

“By what means did the Brethren defend themselves?”

“By patience,” replied Augusta.

“To whom did they apply for help?”

Augusta pointed to heaven.

As Augusta’s answers to all these questions were not considered satisfactory, they next endeavored to sharpen his wits by torturing a German counterfeiter in his presence; and when this mode of persuasion failed, they tortured Augusta himself. They stripped him naked. They stretched him face downwards on a ladder. They smeared his hips with boiling pitch. They set the spluttering mess on fire, and drew it off, skin and all, with a pair of tongs. They screwed him tightly in the stocks. They hung him up to the ceiling by a hook, with the point run through his flesh. They laid him flat upon his back and pressed great stones on his stomach.

It was all in vain. Again they urged him to confess the part that he and the Brethren had played in the great revolt, and again Augusta bravely replied that the Brethren as a whole had taken no part.

At this the King himself intervened. For some months he had been busy enough at Augsburg, assisting the Emperor in his work; but now he sent a letter to Prague, with full instructions how to deal with Augusta. If gentle measures did not succeed, then sterner measures, said he, must be employed. He had three new tortures to suggest. First, he said, let Augusta be watched and deprived of sleep for five or six days. Next, he must be strapped to a shutter, with his head hanging over one end; he must have vinegar rubbed into his nostrils; he must have a beetle fastened on to his stomach; and in this position, with his neck aching, his nostrils smarting, and the beetle working its way to his vitals, he must be kept for two days and two nights. And, third, if these measures did not act, he must be fed with highly seasoned food and allowed nothing to drink.

But these suggestions were never carried out. As the messenger hastened with the King’s note, and the Brethren on the northern frontier were setting out for Poland, Augusta and Bilek were on their way to the famous old castle of Krivoklat. For ages that castle, built on a rock, and hidden away in darkling woods, had been renowned in Bohemian lore. There the mother of Charles IV had heard the nightingales sing; there had many a rebel suffered in the terrible “torture-tower”; and there Augusta and his faithful friend Bilek118 were to lie for many a long and weary day.

They were taken to Krivoklat in two separate wagons. They traveled by night and arrived about mid-day; they were placed in two separate cells, and for sixteen years the fortunes of the Brethren centered round Krivoklat Castle.

If the Bishop had been the vilest criminal, he could not have been more grossly insulted. For two years he had to share his cell with a vulgar German counterfeiter; and the counterfeiter, just for the fun of it, often hit him on the head.

The cell was almost pitch-dark. The window was shuttered within and without, and the merest glimmer from the cell next door struggled in through a chink four inches broad. At meals alone he was permitted half a candle. For bedding he had a leather bolster, a coverlet and what Germans call a “bed-sack.” For food he was allowed two rations of meat, two chunks of bread, and two jugs of barley-beer a day. His shirt was washed about once every two weeks, his face and hands twice a week, his head twice a year, and the rest of his body never. He was not allowed the use of a knife and fork. He was not allowed to speak to the prison attendants. He had no books, no papers, no ink, no news of the world without; and there for three years he sat in the dark, as lonely as the famous prisoner of Chillon. Again, by the King’s command, he was tortured, with a gag in his mouth to stifle his screams and a threat that if he would not confess he should have an interview with the hangman; and again he refused to deny his brethren, and was flung back into his corner.

Krivoklat Castle, where John Augusta was imprisoned in the dungeons for many years.

The delivering angel came in humble guise. Among the warders who guarded his cell was a daring youth who had lived at Litosmyl. He had been brought up among the Brethren. He regarded the Bishop as a martyr. His wife lived in a cottage near the castle; and now, drunken rascal though he was, he risked his life for Augusta’s sake, used his cottage as a secret post office, and handed in to the suffering Bishop letters, books, ink, paper, pens, money and candles.

The Brethren stationed a priest in Krivoklat village. The Bishop was soon as bright and active as ever. By day he buried his tools in the ground; by night he plugged every chink and cranny, and applied himself to his labors. Not yet was his spirit broken; not yet was his mind unhinged. As his candle burned in that gloomy dungeon in the silent watches of the night, so the fire of his genius shone anew in those darksome days of trial and persecution; and still he urged his afflicted Brethren to be true to the faith of their fathers, to hold fast the Apostles’ Creed, and to look onward to the brighter day when once again their pathway would shine as the wings of a dove that are covered with silver and her feathers with yellow gold. He comforted Bilek in his affliction; he published a volume of sermons for the elders to read in secret; he composed a number of stirring and triumphant hymns; and there he penned the noble words still sung in the Brethren’s Church:

Praise God for ever.

Boundless is his favor,

To his Church and chosen flock,

Founded on Christ the Rock.

As he lay in his cell, he pondered much on the sad fate of his Brethren. At one time he heard a rumor that the church was almost extinct. Some, he knew, had fled to Poland. Some had settled in Moravia. Some, robbed of lands and homes, were roaming the country as peddlers or earning a scanty living as farm laborers. And some, alas! had lowered the flag and joined the Church of Rome.

And yet Augusta had never abandoned hope. For ten years, despite a few interruptions, he kept in almost constant touch, not only with his own Brethren, but also with the Protestant world at large. He was still, he thought, the loved and honored leader; he was still, in his mind, the mightiest religious force in the land; and now, in his dungeon, he sketched a plan to heal his country’s woes and form the true disciples of Christ into one grand national Protestant army against which both Pope and Emperor would for ever contend in vain.

As he lay in his dungeon forming plans for the Church he loved so well, it slowly dawned upon Augusta that his Brethren were ceasing to trust him, and that the sun of his power, which had shone so brightly, was now sloping slowly to its setting. He heard of one change after another taking place without his consent. He heard that the Council had condemned his sermons as too learned and dry for the common people, and that they had altered them to suit their own opinions. He heard that his hymns, which he had desired to see in the new Hymn-book, had been mangled in a similar manner. The Brethren did not even tell him what they were doing. They simply left him out in the cold. What he himself heard, he heard by chance, and that was the “most unkind cut of all.” His authority was gone; his position was lost—new bishops had been ordained to take his place. His hopes were blasted; and his early guidance, his entreaties, his services, his sufferings were all, he thought, forgotten by an ungrateful church.

As Augusta heard of all these changes, a glorious vision rose before his mind. At first he was offended, quarreled with the Brethren, and declared the new Bishops invalid. But at last his better feelings gained the mastery. He would not sulk like a petted child; he would render his Brethren the greatest service in his power. He would fight his way to liberty; he would resume his place on the bridge, and before long he would make the Big Group the national Church of Bohemia.

So Augusta appealed for liberty. The issue before him was now perfectly clear. There was one road to freedom and one only. He must sign the form of recantation in full. The form was drastic. He must renounce all his previous religious opinions. He must acknowledge the Roman Catholic Church and submit to her in all things. He must eschew the gatherings of Waldensians, Picards, and all other “apostates”, denounce their teaching as depraved, and recognize the Church of Rome as the one true Church of Christ. He must labor for the unity of the Church and endeavor to bring his Brethren into the fold. He must never again interpret the Scriptures according to his own understanding, but submit rather to the exposition and authority of the Holy Roman Church, which alone was fit to decide on questions of doctrine. He must do his duty by the King, obey him and serve him with zeal as a loyal subject. And finally he must write out the whole recantation with his own hand, take a public oath to keep it, and have it signed and sealed by witnesses.

Augusta refused point blank. His hopes of liberty vanished. His heart sank in despair. “They might as well,” said Bilek, his fellow-prisoner, “have asked him to walk on his head.”

Another Route

But here Lord Sternberg, Governor of the Castle, suggested another path. If Augusta, said he, would not join the Church of Rome, perhaps he would at least join the Utraquists—the Hussites. He had been a Utraquist in his youth; the Brethren were Utraquists under another name; and all that Augusta had to do was to give himself his proper name,119 and his dungeon door would fly open.

A series of ambiguously written “confessions” was extended by Augusta. But his captors could see through them all. Augusta sank back exhausted in his cell. But the kindly Governor was still resolved to smooth the way for his prisoners. “I will not rest,” he said, “till I see them at liberty.” He suggested that Augusta should have an interview with the Jesuits!

“What would be the good of that?” said Augusta. “I should be like a little dog in the midst of a pack of lions. I pray you, let these negotiations cease. I would rather stay where I am. It is clear there is no escape for me unless I am false to my honor and my conscience. I will never recant nor act against my conscience. May God help me to keep true till death.”

At last, however, Augusta gave way, attended mass, with Bilek, in the castle chapel, and consented to an interview with the Jesuits, on condition that Bilek should go with him, and that he should also be allowed another interview with the Utraquists.

The day for the duel arrived. The chosen spot was the new Jesuit College at Prague. As they drove to the city, both Augusta and Bilek were allowed to stretch their limbs and even get out of sight of their guards. At Prague they were allowed a dip in the Royal Bath. It was the first bath they had had for fourteen years, and the people came from far and near to gaze upon their scars.

The meeting might as well have been an attempt at reconciling a cat and dog. Augusta was not about to become Catholic. The Jesuits were not the least interested in acknowledging the Big Group as a legitimate church.

The Jesuits reported him hard in the head, and had him sent back to his cell.

For two more years he waited in despair, and then he was brought to the White Tower again, and visited by two Utraquist Priests, Mystopol and Martin. The last chance, they told him, had now arrived. They had come as messengers from the Archduke Ferdinand and from the Emperor himself.

“I know,” said one of them, “on what you are relying and how you console yourself, but I warn you it will avail you nothing.”

They indeed knew Augusta, and should not have wasted their time with him. Neither they nor he were willing to give ground. However, Augusta did throw them an offer: Why doesn’t the Utraquist Church join hands with the Big Group, and then all Bohemia would join together to support them?

At this grand scheme, Augusta lost support from both sides.

“You shift about,” wrote the Big Group brethren, “in a most remarkable manner. You make out the Utraquist Church to be different from what it really is, in order to keep a door open through which you may go.” In their judgment he was nothing but an ambitious schemer. If his scheme were carried out, they said, he would not only be First Elder of the Brethren’s Church, but administrator of the whole united Church.

And to the Utraquists, he was trying to connive his way out of the White Tower dungeon.

At last, however, King Maximilian interceded with the Emperor in his favor, and Augusta was set free on the one condition that he would not preach in public.120 His hair was white; his beard was long; his brow was furrowed; his health was shattered; and he spent his last days amongst the Brethren, a defeated and broken-hearted man. He was restored to his old position as First Elder; he settled down again at Mlada Boleslav; and yet somehow the old confidence was never completely restored.121

John Blahoslav (1523-1571) was a Unity historian and bishop.

In vain he upheld his daring scheme of union. John Blahoslav opposed him to the teeth. For the time, at least, John Blahoslav was in the right. Augusta throughout had made one fatal blunder. As the Utraquists were now more Protestant in doctrine, he thought that they had begun to love the Brethren. The very contrary was the case.

Despised by friend and foe alike, the old white-haired Bishop tottered to the silent tomb. “He kept out of the way,” says the sad old record, “as long as he could; he had been among us long enough.”

The Golden Age of Fool's Gold 1572-1603

As the Emperor Maximilian II set out from the Royal Castle in Prague for a drive, he met a baron famous in all the land. The baron was John von Zerotin, the richest member of the Big Group’s Church in Moravia. He had come to Prague on very important business. His home lay at Namiest, in Moravia. He lived in a stately castle, built on two huge crags, and surrounded by the houses of his retainers and domestics. His estate was twenty-five miles square. He had a lovely park of beeches, pines and old oaks. He held his court in kingly style. He had gentlemen of the chamber of noble birth. He had pages and secretaries, esquerries and masters of the chase. He had valets, lackeys, grooms, stable-boys, huntsmen, barbers, watchmen, cooks, tailors, shoemakers, and saddlers. He had sat at the feet of Blahoslav, the learned Church historian: he kept a Court Chaplain, who was, of course, a pastor of the Big Group’s Church; and now he had come to talk things over with the head of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Emperor offered the Baron a seat in his carriage. The “Brother” and the Emperor drove on side by side.

From people who practiced community of goods and gave their excess to the poor, the Unity of Brothers came to include men like John von Zerotin, owner of the above castle with it surrounding estate of 25 miles square.

“I hear,” said the Emperor, “that the Picards are giving up their religion and going over to the Utraquists.”

The Baron was astounded. He had never, he said, heard the slightest whisper that the Brethren intended to abandon their own Confessions.

“I have heard it,” said the Emperor, “as positive fact from Baron Hassenstein himself.”

“It is not true,” replied Zerotin.

“What, then,” said the Emperor, “do the Utraquists mean when they say that they are the true Hussites, and wish me to protect them in their religion?”

“Your gracious Majesty,” replied Zerotin, “the Brethren, called Picards, are the true Hussites122: they have kept their faith unsullied, as you may see yourself from the Confession they presented to you.”

The Emperor looked puzzled. He was waxing old and feeble, and his memory was failing.

“What!” he said, “have the Picards got a Confession?”

He was soon to hear the real truth of the matter. For some months there had sat in Prague a committee of learned divines, who had met for the purpose of drawing up a National Protestant Bohemian Confession. The dream of John Augusta seemed to be coming true. The Big Group took their part in the proceedings. “We are striving,” said Slawata, one of their deputies, “for peace, love and unity. We have no desire to be censors of dogmas. We leave such matters to theological experts.” The Confession was prepared, read out at the Diet, and presented to the Emperor. It was a compromise between the teaching of Luther and the teaching of the Brethren. In its doctrine of justification by faith, it followed the teaching of Luther:123 in its doctrine of the Lord’s Supper it inclined to the view of the Brethren. The Emperor attended the Diet in person, and made a notable speech.

“I promise,” he said, “on my honor as an Emperor, that I will never oppress or hinder you in the exercise of your religion; and I pledge my word in my own name and also in the name of my successors.”

Let us try to grasp the meaning of this performance. As the Edict of St. James was still in force, the Unity of Brothers, in the eyes of the law, were still heretics and rebels; they had no legal standing in the country; and at any moment the King in his fury might order them to quit the land once more. But the truth is that the King of Bohemia was now a mere figurehead. The real power lay in the hands of the barons. The barons were Protestant almost to a man.

It was the age of material prosperity. As the sun of “freedom” shone upon their way, the Big Group drifted further still from the “ascetic” ideas of Peter and Gregory. They had now all classes in their ranks. They had seventeen rich and powerful barons, of the stamp of John Zerotin; they had over a hundred and forty knights; they had capitalists, flourishing tradesmen, mayors, and even generals in the Army, and the Lord High Chamberlain now complained that two-thirds of the people in Bohemia were Big Group members.

The Letter of Majesty

Of all the members of the Big Group’s Church in Bohemia, the most powerful and the most discontented was Baron Wenzel von Budowa. He was now fifty-six years of age. He had traveled in Germany, Denmark, Holland, England, France and Italy. He had studied at several famous universities. He had made the acquaintance of many learned men. He had entered the Imperial service, and served as ambassador at Constantinople. He had mastered Turkish and Arabic, had studied the Mohammedan religion, had published the Al Koran in Bohemian, and had written a treatise denouncing the creed and practice of Islam as Satanic in origin and character.

He belonged to the Emperor’s Privy Council, and also to the Imperial Court of Appeal. He took part in theological controversies, and preached sermons to his tenants. He was the bosom friend of Baron Charles von Zerotin, the leading Big Group member of Moravia. He corresponded, from time to time, with the struggling Protestants in Hungary, and had now become the recognized leader, not only of the Brethren, but of all “evangelicals” in Bohemia.

He had one great purpose to attain. As the Brethren had rendered such signal service to the moral welfare of the land, it seemed to him absurd and unfair that they should still be under the ban of the law and still be denounced in Catholic pulpits as children of the devil. He resolved to remedy the evil. The Emperor, Rudolph I, paved the way. He was just the man that Budowa required. He was weak in body and in mind. He had ruined his health, said popular scandal, by indulging in dissolute pleasures. His face was shriveled, his hair bleached, his back bent, his step tottering. He was too much interested in astrology, gems, pictures, horses, antique relics and similar curiosities to take much interest in government; he suffered from religious mania, and was constantly afraid of being murdered.

And now he committed an act of astounding folly. He first revived the Edict of St. James, ordered the nobles throughout the land to turn out all Protestant pastors, and sent a body of armed men to close the Big Group’s House at Mlada Boleslav; and then, having disgusted two-thirds of his loyal subjects, he summoned a Diet, and asked for money for a crusade against the Turks.

This was more than Wenzel could endure. He attended the Diet, and made a brilliant speech. He had nothing, he said, to say against the Emperor. He would not blame him for reviving the musty Edict. For that he blamed some secret disturbers of the peace. If the Emperor needed money and men, the loyal knights and nobles of Bohemia would support him. But that support would be given on certain conditions. If the Emperor wished his subjects to be loyal, he must first obey the law of the land himself. “We stand,” he said, “one and all by the Confession of 1575, and we do not know a single person who is prepared to submit to the Consistory at Prague.” He finished, wept, prepared a petition, and sent it in to the poor invisible Rudolph. And Rudolph replied as Emperors sometimes do. He replied by closing the Diet.

Again, however, six years later, Budowa returned to the attack. He was acting, not merely on behalf of the Brethren, but on behalf of all Protestants in the country. And this fact is the key to the situation. As we follow the dramatic story to its sad and tragic close, we must remember that from this time onward the Brethren, for all intents and purposes, had almost abandoned their position as a separate Church, and had cast in their lot with the other Protestants in Bohemia. They were striving now for the recognition, not of their own Confession of Faith, but of the general Bohemian Protestant Confession presented to the Emperor, Maximilian II. And so, Budowa became a national hero. He called a meeting of Lutherans and Brethren in the historic “Green Saloon,” prepared a resolution demanding that the Protestant Confession be inscribed in the Statute Book, and, followed by a crowd of nobles and knights, was admitted to the sacred presence of the Emperor.

Again the Diet was summoned. The hall was crammed, and knights and nobles jostled each other in the corridors and in the square outside. For some weeks the Emperor, secluded in his cabinet, held to his point like a hero. The debate was conducted in somewhat marvelous fashion. There, in the Green Saloon, sat the Protestants, preparing proposals and petitions. There, in the Archbishop’s palace, sat the Catholics, rather few in number, and wondering what to do. And there, in his chamber, sat the grizzly, rickety, imperial Lion, consulting with his councilors, Martinic and Slawata, and dictating his replies. And then, when the king had his answer ready, the Diet met in the Council Chamber to hear it read aloud. His first reply was now as sharp as ever. He declared that the faith of the Church of Rome was the only lawful faith in Bohemia. “And as for these Brethren,” he said, “whose teaching has been so often forbidden by royal decrees and decisions of the Diet, I order them, like my predecessors, to fall in with the Utraquists or Catholics, and declare that their meetings shall not be permitted on any pretense whatever.”

In vain the Protestants, by way of reply, drew up a monster petition, and set forth their grievances in detail. They suffered, they said, not from actual persecution, but from nasty insults and petty annoyances. They were still described in Catholic pulpits as heretics and children of the devil. They were still forbidden to honor the memory of Huss. They were still forbidden to print books without the consent of the Archbishop. The King snapped them short . He told the estates to end their babble, and again closed the Diet.

The blood of Budowa was up. The debate, thought he, was fast becoming a farce. The King was fooling his subjects. The King must be taught a lesson. As the Diet broke up, he stood at the door, and shouted out in ringing tones: “Let all who love the King and the land, let all who care for unity and love, let all who remember the zeal of our fathers, meet here at six tomorrow morn.”

He spent the night with some trusty allies, prepared another declaration, met his friends in the morning, and informed the King, in language clear, that the Protestants had now determined to win their rights by force. And Budowa was soon true to his word. He sent envoys asking for help to the King’s brother Matthias, to the Elector of Saxony, to the Duke of Brunswick, and to other Protestant leaders. He called a meeting of nobles and knights in the courtyard of the castle, and there, with heads bared and right hands upraised, they swore to be true to each other and to win their liberty at any price, even at the price of blood.124 He arranged for an independent meeting in the town hall of the New Town. The King forbade the meeting. What better place, replied Budowa, would His Majesty like to suggest? As he led his men across the long Prague bridge, he was followed by thousands of supporters. He arrived in due time at the square in front of the hall. The Royal Captain appeared and ordered him off. The crowd jeered and whistled the Captain away.

And yet Budowa did not desire to be a “vulgar” rebel. He insisted that every session in the hall should be begun and ended with prayer. He informed the King, again and again, that all he wished was liberty of worship for Protestants. He did his best to put an end to the street rows, the drunken brawls, that now disgraced the city.

For the third time the King summoned the Diet. The last round in the terrible combat now began. He ordered the estates to appear in civilian’s dress. They arrived armed to the teeth. He ordered them to open the proceedings by attending mass in the Cathedral. The Catholics alone obeyed; the Protestants held a service of their own; and yet, despite these danger signals, the King was as stubborn as ever, and again he sent a message to say that he held to his first decision. The Diet was thunderstruck, furious, desperate.

“We have had enough of useless talk,” said Count Matthias Thurn; “it is time to take to arms.”125 The long fight was drawing to a finish. As the King refused to listen, the members of the Diet, one and all, Protestants and Catholics alike, prepared an ultimatum demanding that all evangelical nobles, knights, citizens and peasants should have full and perfect liberty to worship God in their own way, and to build schools and churches on all Royal estates; and, in order that the King might realize the facts of the case, Budowa formed a Board of thirty directors, of whom fourteen were of the Big Group, raised an army in Prague, and sent the nobles flying through the land to levy money and troops. The country, in fact, was now in open revolt. And thus, at length compelled by brute force, the poor old King gave way, and made his name famous in history by signing the Letter of Majesty and granting full religious liberty to all adherents of the Bohemian National Protestant Confession. All adherents of the Confession could worship as they pleased, and all classes, except the peasantry, could build schools and churches on Royal estates. “No decree of any kind,” ran one sweeping clause, “shall be issued either by us or by our heirs and succeeding kings against the above established religious peace.”

The delight in Prague was boundless. The Letter of Majesty was carried through the streets in grand triumphal procession. The walls were adorned with flaming posters. The bells of the churches were rung. The people met in the Church of the Holy Cross, and there sang jubilant psalms of thanksgiving and praise. The King’s couriers posted through the land to tell the gladsome news; the letter was hailed as the heavenly herald of peace and goodwill to men; and Budowa was adored as a national hero, and the redresser of his people’s wrongs.

But…

As Matthias was growing old and feeble, it was time to choose his successor; and Matthias, therefore, summoned a Diet, and informed the Estates, to their great surprise, that all they had to do now was to accept as King his adopted son, Ferdinand Archduke of Styria. At first the Diet was thunderstruck. They had met to choose their own King. They intended to choose a Protestant, and now they were commanded to choose this Ferdinand, the most zealous Catholic in Europe. And yet, for some unknown reason, the Diet actually yielded. They surrendered their elective rights; they accepted Ferdinand as King, and thus, at this critical point in the history of the country, they allowed a Catholic devotee to become the ruler of a Protestant people.

In Ferdinand, they had accepted a man who was pledged to fight for the Church of Rome with every breath of his body. He was a man of fervent piety. He was a pupil of the Jesuits. He regarded himself as the divinely appointed champion of the Catholic faith. He had already stamped out the Protestants in Styria. He had a strong will and a clear conception of what he regarded as his duty. He would rather, he declared, beg his bread from door to door, with his family clinging affectionately around him, than allow a single Protestant in his dominions. “I would rather,” he said, “rule over a wilderness than over heretics.”

But what about his oath to observe the Letter of Majesty? Should he take the oath or not? If he took it he would be untrue to his conscience; if he refused he could never be crowned King of Bohemia. He consulted his friends the Jesuits. They soon eased his conscience. It was wicked, they said, of Rudolph II to sign such a monstrous document; but it was not wicked for the new King to take the oath to keep it. And, therefore, Ferdinand took the oath, and was crowned King of Bohemia.

“We shall now see,” said a lady at the ceremony, “whether the Protestants are to rule the Catholics or the Catholics the Protestants.”

The Protestants summoned their assembly, prepared a petition, and sent it off to Matthias. He replied that their assembly was illegal. He refused to remedy their grievances. “The Defenders” were goaded to fury. At their head was a violent man, Henry Thurn. He resolved on open rebellion. He would have the new King Ferdinand dethroned and have his two councilors, Martinic and Slawata, put to death. It was the 23rd of May, 1618. At an early hour on that fatal day, the Protestant Convention met in the Hradschin, and then, a little later, the fiery Thurn sallied out with a body of armed supporters, arrived at the Royal Castle, and forced his way into the Regent’s Chamber, where the King’s Councllors were assembled.

Prague Castle, the largest castle in the world. Imagine getting thrown out of one of the top floor windows, in "good old Bohemian fashion”, at the command of a member of the Unity of Brothers.

There, in a corner by the stove, sat Martinic and Slawata. There, in that Regent’s Chamber, began the cause of all the woe that followed. There was struck the first blow of the Thirty Years’ War. As Thurn and his henchmen stood in the presence of the two men, who, in their opinion, had done the most to poison the mind of Matthias, they felt that the decisive moment had come. The interview was stormy. Voices rang in wild confusion. The Protestant spokesman was Paul von Rican. He accused Martinic and Slawata of two great crimes. They had openly broken the Letter of Majesty, and had dictated King Matthias’s last reply. He appealed to his supporters crowded into the corridor outside.

“Yes, yes,” shouted the crowd.

“Into the Black Tower with them,” said some.

“No, no,” said Rupow, a member of the Big Group’s Church, “Out of the window with them, in the good old Bohemian fashion.”

At this signal, agreed upon before, Martinic was dragged to the window. He begged for a father confessor.

“Commend your soul to God,” said someone. “Are we to allow any Jesuit scoundrels here?”

“Jesus! Mary!” he screamed.

He was flung headlong from the window. He clutched at the windowsill. A blow came down on his hands. He had to let go, and down he fell, seventy feet, into the moat below.

“Let us see,” said someone, “whether his Mary will help him.”

He fell on a heap of soft rubbish. He scrambled away with only a wound in the head.

“His Mary has helped him!” cried one of the men.

They now flung Slawata out of the window, and his secretary Fabricius after him. Not one of the three was killed, not one was even maimed for life, and through the country the rumor spread that all three had been delivered by the Virgin Mary.

From that moment war was inevitable. The Protestants elected Frederick, Elector Palatine, and son-in-law of James I of England, as King of Bohemia; and they ordered the Jesuits out of the kingdom.

There was a strange scene in Prague when these Jesuits departed. They formed in procession in the streets, and, clad in black, marched off with bowed heads and loud wailing.

For the moment the Protestants of Prague were wild with joy. In the great Cathedral they pulled off the ornaments and destroyed costly pictures.

What happened next is unclear: Details are not needed, and are scarce. We know that the Catholics were now united and the Protestants quarreling with each other; we know that Ferdinand was prompt and vigorous, and the new King Frederick slack; and we know, finally, that the Catholic army, commanded by the famous general Tilly, was far superior to the Protestant army under Christian of Anhalt.

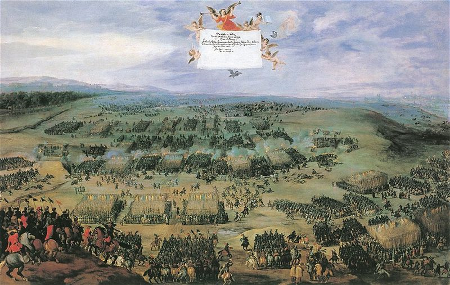

The battle of White Mountain, just outside of Prague: "Christians" fighting other "Christians" for control of the government.

At last the Catholic army appeared before the walls of Prague. The battle of the White Hill was fought.126 The new King was entertaining some ambassadors to dinner in the city. The Protestant army was routed, the new King fled from the country.

The conqueror consisted in a certain Prince Lichtenstein. He was made regent of Prague, and was entrusted with the duty of restoring the country to order. He set about his work in a cool and methodical manner. He cleared the rabble out of the streets. He recalled the Jesuits. He ordered the Big Group out of the kingdom. He put a Roman Catholic priest into every church in Prague; and then he made the strange announcement that all the rebels, as they were called, would be freely pardoned, and invited the leading Protestant nobles to appear before him at Prague. They walked into the trap like flies into a cobweb.

If the nobles had only cared to do so, they might all have escaped after the battle of White Mountain. Tilly, the victorious general, had purposely given them time to do so. But for some reason they nearly all preferred to stay. And now Lichtenstein had them in his grasp. He had forty-seven leaders arrested in one night. He imprisoned them in the castle tower, had them tried and condemned, obtained the approval of Ferdinand, and then, while some were pardoned, informed the remaining twenty-seven that they had two days in which to prepare for death. They were to die on June 21st. Among those leaders were about a dozen Big Group Brethren.

The Last of the Bohemian Brethren

We have arrived at the last act of the tragedy. We have seen the grim drama develop, and when the curtain falls the stage will be covered with corpses and blood.

Prague was divided into two parts, the Old Town and the New Town. In the middle of the Old Town was a large open space, called the Great Square. On the west side of the Great Square stood the Council House, on the east the old Teyn Church where the preachers in days gone by had thundered out against carnality. The condemned prisoners, half of whom were Big Group Brethren, were in the Council House: in front of their window was the scaffold, draped in black cloth, twenty feet high, and twenty-two yards square; from the window they stepped out on to a balcony, and from the balcony to the scaffold ran a short flight of steps. In that Great Square, and on that scaffold, we find the scene of our story.

27 crosses are inlaid into the cobblestones of Prague's Old Town Square in memory of the 27 Protestant and Unity men who died on “The Day of Blood”, decapitated for rebellion against the king.

When early in the morning of Monday, June 21st, the assembled prisoners looked out of the windows of their rooms to take their last view of earth, they saw a splendid, a brilliant, a gorgeous, but to them a terrible scene. They saw God’s sun just rising in the east and reddening the sky and shining in each other’s faces; they saw the dark black scaffold bathed in light, and the squares of infantry and cavalry ranged around it; they saw the eager, excited throng, surging and swaying in the Square below and crowding on the house-tops to right and left; and they saw on the further side of the square the lovely twin towers of the old Teyn Church, where Gregory had knelt and Rokycana had preached in the brave days of old. As the church clocks chimed the hour of five, a gun was fired from the castle; the prisoners were informed that their hour had come, and were ordered to prepare for their doom; and the new Regent Lichtenstein and the magistrates stepped out on to the balcony, an awning above them to screen them from the rising sun.

As there was now a long morning’s work to be done, that work was begun at once. The heads of the victoms fell off the block in quick succession while the trumpets brayed and the drums beat an accompaniment. Grim and ghastly was the scene in that Great Square in Prague, on that bright June morning about 400 hundred years ago.

Each of the condemned had fortified themselves to look the waiting angel of death in the face. As they sat in their rooms the evening before—a sabbath evening it was—they had all, in one way or another, sought God in prayer. In one room the prisoners had taken the Communion together, in another they joined in singing psalms and hymns; in another they had feasted in a last feast of love. Among these were various shades of faith—Lutherans, Calvinists, Utraquists, Big Group brethren; but now all differences were laid aside, for all was nearly over now.127 One laid the cloth, and another the plates; a third brought water and a fourth said the simple grace. As the night wore on they lay down on tables and benches to snatch a few hours of that troubled sleep which gives no rest. At two they were all broad awake again, and again the sound of psalms and hymns was heard; and as the first gleams of light appeared each dressed himself as though for a wedding, and carefully turned down the ruffle of his collar so as to give the executioner no extra trouble.

Swiftly, in order, and without much cruelty, the gory work was done. The morning’s program had all been carefully arranged. At each corner of the square was a squad of soldiers to hold the people in awe, and to prevent an attempt at rescue. One man, named Mydlar, was the executioner; and, being a Protestant,128 he performed his duties with as much decency and humanity as possible. He used four different swords, and was paid about £100 for his morning’s work. With his first sword he beheaded eleven; with his second, five; with his two last, eight. The first of these swords is still to be seen at Prague,129 and has the names of its eleven victims engraved upon it. Among these names is the name of Wenzel von Budowa. In every instance Mydlar seems to have done his duty at one blow. At his side stood an assistant, and six masked men in black. As soon as Mydlar had severed the neck, the assistant placed the dead man’s right hand on the block; the sword fell again; the hand dropped at the wrist; and the men in black, as silent as night, gathered up the bleeding members, wrapped them in clean black cloth, and swiftly bore them away.

The name of Budowa was second on the list. “My heart impelled me to come.” he said. “To forsake my country and its cause would have been sinning against my conscience. Here am I, my God, do unto your servant as seems good unto You. I would rather die myself than see my country die.”130

A few days before his head rolled off, on the Monday morning, he was given another chance to deny his faith. The Jesuits came to see him.

“We have come to save my lord’s soul,” they said, “and to perform a work of mercy.”

“Dear fathers,” replied Budowa, “I thank my God that His Holy Spirit has given me the assurance that I will be saved through the blood of the Lamb.” He appealed to the words of St. Paul: “I know whom I have believed: henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, shall give me at that day.”

“I go,” he declared, “in the garment of righteousness; thus arrayed shall I appear before God.”

Alone, with firm step he strode to the scaffold, stroking proudly his silver hair and beard.

“You old grey head of mine,” said he, “you are highly honored; you shalt be adorned with the Martyr-Crown.”131

The newly-cropped heads were spitted on poles in the city, there to grin for full ten years as a warning to all rebels.

Forced Out

Meanwhile, the Brethren were expelled from Bohemia. It is a striking proof of the influence of the Brethren that Ferdinand turned his attention to them before he troubled about the other Protestants. They had been the first in moral power; they had done the most to spread the knowledge of the Bible; they had produced the greatest literary men of the country; and, therefore, now they must be the first to go. What actually happened to many of the Brethren during the next few years no tongue can tell. But we know enough. We know that Ferdinand cut the Letter of Majesty in two with his scissors. We know that 36,000 families left Bohemia and Moravia—among them 1400 families of the “nobility”—and that the population of Bohemia dwindled from three million to one. Over three hundred castles and forts, one hundred towns, and eleven thousand villages disappeared from the face of the earth.

We know that about one-half of the property—lands, houses, castles, churches—passed over into the hands of the King. We know that the University of Prague was handed over to the Jesuits. We know that the scandalous order was issued that all Protestant married ministers who consented to join the Church of Rome might keep their wives by passing them off as cooks. We know that villages were sacked; that Kralitz Bibles, Hymn-books, Confessions, Catechisms, and historical works of priceless value—among others Blahoslav’s “History of the Brethren”132—were burned in thousands; and that almost nearly every trace of the Brethren was swept out of the land.

We know that some of the Brethren were hacked in pieces, that some were tortured, that some were burned alive, that some swung on gibbets at the city gates and at the country cross-roads among the carrion crows. For six years Bohemia was a field of blood, and Spanish soldiers, drunk and raging, slashed and pillaged on every hand. “Oh, to what torments,” said a clergyman of that day, “were the promoters of the Gospel exposed! How they were tortured and massacred! How many virgins were violated to death! How many respectable women abused! How many children torn from their mothers’ breasts and cut in pieces in their presence! How many dragged from their beds and thrown naked from the windows! Good God! What cries of woe we were forced to hear from those who lay upon the rack, and what groans and terrible outcries from those who besought the robbers to spare them for God’s sake.”

It was thus that the Brethren, at the point of the sword, were driven from hearth and home: thus that they fled before the blast and took refuge in foreign lands; thus, amid bloodshed, and crime, and cruelty, and nameless torture, that the Big Group of the Bohemian Brethren bade a sad farewell to the land of its birth, and practically disappeared from the eyes of mankind.

Behold What Change!

Let us review the story of the Unitas Fratrum. What a marvelous change had come upon it! It began in the quiet little valley of Kunvald: it ended in the noisy streets of Prague. It began in peace and brotherly love: it ended amid the tramp of horses, the clank of armor, the swish of swords, the growl of artillery, the whistle of bullets, the blare of trumpets, the roll of drums, and the moans of the wounded and the dying. It began in the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount: it ended amid the ghastly horrors of war.

Word was sent to the Pope at Rome that the Unity of Brothers was no more.

Go to Part 6 The Hidden Seed106Peter Chelcicky’s tract, likely. But there may have been others tracts with the same name.

107 That is, more than the Utraquists did.

108Such words of praise, for a compromised lifestyle. Yet Luther seemed not to realized that his very doctrine inhibited his followers from attaining such ‘high’ morality!

109 In the year 1526

110 Nov. 11th, 1535

111And who changed so as to make this formerly inviable union possible?

112 Not the original discipline of Chelcicky or Gregory, of course, but the modified of Luke of Prague.

113 April 24th, 1547.

114 This goes to show that not all who die a ‘martyr’s death’ will be ready to meet God on the judgment day.

115 May, 1548.

116 This was the independent congregation of believers that also practiced the Sermon on the Mount.

117 April 25th, 1548.

118One historian writes of this man: “If ever a man had just cause to hate the Church of Rome, it was surely this humble friend of Augusta; and yet he wrote a full account of their dreary years in prison without saying one bitter word against his persecutors and tormentors. From this point of view, his book is delightful. It is full of piety, of trust in God, of vivid dramatic description; it has not a bitter word from cover to cover; and thus it is a beautiful and precious example of the broad and charitable spirit of the Unity of Brothers.”

119Is not it amazing how those outside of the church have a better understanding of things than those inside? Sternburg recognized that the Unity of Brothers was not a whole ways off from the Ultraquists.

120 In 1564.

121His physical condition pretty well describes the spiritual condition of the Big Group.

122Notice how the big Group now looked to John Huss’ example instead Peter Chelcicky’s.

123Hear the death bells tolling?

124 Remember now, that this is the “Big Group” of the Unity of Brothers that Chelcicky and Gregory had guided 100 years earlier…

125If we remember back to the beginning of our story, the Bohemians were debating non-resistance, and finally decided to defend themselves. Here they are taking the offensive.

126 November 8th, 1620

127And there really was very little difference now anyways.

128 Little details such as this show the glaring inconsistency of the so-called Protestant Reformation…

129Since this was written about a century ago, I do not know if it is still in existence.

130Here we see patriotism for a political realm, instead of “patriotism” for righteousness, peace and joy.

131A sad reminder that not all “martyrs” will go to heaven, inspite of the fact that they speak good words and have falsely convinced themselves of being righteous. They that DO righteousness are righteous, not those who believe they are righteous.

132Blahoslav wrote a large history of the Unitas Fratrum, but no copies have been found since this destruction.